I Refuse to Return to the Office After My Coworker’s ‘Prank’ Revealed His Darkest Secret

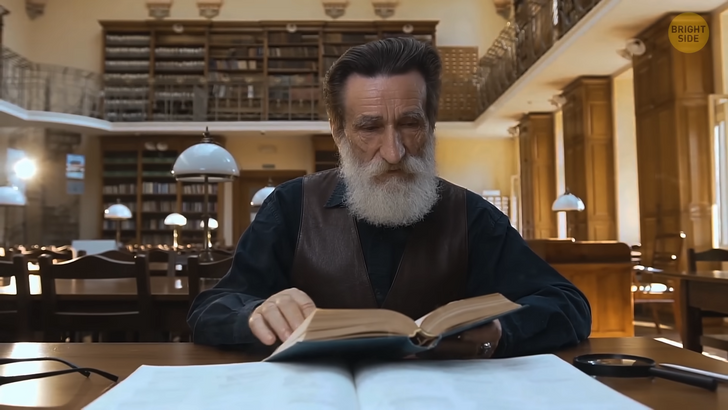

Today we’re going on an art history trip. Our main focus is to unravel the mystery of whether or not ancient statues have always been white. We’ll visit museums and even time travel to try and get a glimpse of what these statues were really like back in the day.

To kick off our tour, we land in New York. We climb the famous steps of the MET, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and walk inside this enormous museum. You walk down the aisle and get to the room where one of the world’s biggest collections of ancient Greek and Roman statues is held.

Admiring the large array of statues, one thing seems evident. They are mainly white. It makes sense since their primary material is white marble. For centuries, historians, archeologists, and researchers, in general, have always taken this fact for granted. Weren’t these statues always white? Until recent decades, this wasn’t something that people discussed.

But, in the 1980s, researchers unearthed an ancient Greek statue that was clearly pigmented. This new discovery made them wonder: were all ancient statues painted? Let’s take a close look at this work of art. This 3rd Century BCE Greek statue was discovered to be almost entirely painted, still in its original form. You don’t have to look too hard to notice that the statue still carries some of its original pink colors, with some shades of blue and red paint as well.

The thing is: this statue is not an exception. It’s the norm! As it turns out, ancient civilizations did paint their sculptures with bright and vivid colors. But somewhere along our historic timeline, this information got lost. According to researchers, pigmenting sculptures was a way of bringing their representations closer to real life. We live in bright colors, so art might as well reflect that, right? Right!

So let’s take a few steps back to understand what happened. So, why are our museum’s galleries filled with white statues as far as the eye could see? You might have heard of Michelangelo. It’s a famous Italian sculptor who carved the iconic David and painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo was one of the most emblematic painters of the Renaissance.

The Renaissance was a historical period when European artists, philosophers, and scientists developed a renewed interest in the creations of Ancient Greece and Rome. Artists like Michelangelo studied a series of Roman sculptures. Like this one: the Laocoön [Lay-OK-oh-ON] and his sons.

They fell in love with their lifelike figures and pristine white marble. The one thing they didn’t know — and didn’t have the technology to know — was if the colored pigments from those sculptures had faded. After all, they were found after years of being buried or left in the open air. It’s speculated that this statue, the Laocoön, had colored snakes and mantles, for example.

When the renaissance artists set out to pay homage to ancient artists, they left their masterpieces bare too. They carved directly onto the marble and left them white, without pigmentation — probably because that’s the way they thought things were done in the old days. The works of Michelangelo and his peers influenced a whole generation of sculptors after that. So this way of doing art traveled to modern times, without much questioning. However, evidence of color pigments in ancient statues is abundant.

Some researches show that scholars have known for at least a century that ancient sculptures weren’t originally all white. Other studies suggest that this discovery might have happened even earlier! In the early 1980s, archeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann made a huge discovery. During his time as a student at the Ludwig Maximilian University, in Munich, he developed a technology that was able to detect polychromy in ancient samples of Greek statues.

Polychromy is the art of painting in several colors. Anyways, he was taken aback by his discovery and confused as to why and how other researchers and archeologists weren’t talking about this. As it happens, the first discovery that ancient statues weren’t all that white happened a long time ago, way before Vinzenz was born.

It happened during the unearthing of Pompeii, back in the 1700s. As you may know, the city of Pompeii, in southern Italy, was completely covered in lava after the sudden eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The city was destroyed, but the clouds of ashes that arose from the lava, managed to preserve a lot of the city’s structure through time. Thankfully for art historians and archeologists, Pompeii became a digging ground for understanding Ancient Rome.

Researchers found several conserved frescoes that depicted scenes of daily Roman life. In one of these paintings, an artist is seen painting a sculpture. This fact was recorded by a very famous art historian known as Johann Joachim Winkelmann. He’s also considered the father of art history.

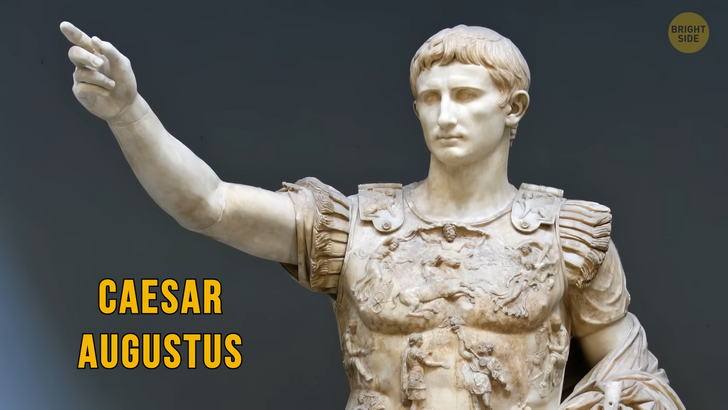

Now, let’s take a closer look at another famous statue. To see this one in person, you’ll have to fly all the way to Rome and visit the Vatican Museums. This statue you’re looking at is a classic representation of Caesar Augustus. In case you didn’t know, he was the founder of the Roman Empire and the first emperor of Rome. He’s important.

This sculpture you’re seeing is called the Augustus of Prima Porta. You may have seen this before, probably in a history textbook. The thing is, it’s always depicted in its white marble form. But according to an archeological finding from the 1860s, the original statue was way much more colorful than that.

According to archeologists, the statue of Augustus de Prima Porta had a crimson tunic, yellow armor, and a purple mantle. It’s important to keep in mind that colors weren’t made artificially as they are today. Artists could only produce color from natural resources. So purple, for example, was an extremely difficult color to make. Back in the day, they derived purple from the mucus of a rare species of snail.

Meaning that anyone who used the color purple to pigment their art and clothes was powerful and wealthy. Well, this looks like enough proof to me that ancient statues weren’t always white. But as we can judge by the look of our modern museums, there didn’t seem to exist enough interest in the art community to further explore polychromy on ancient statues.

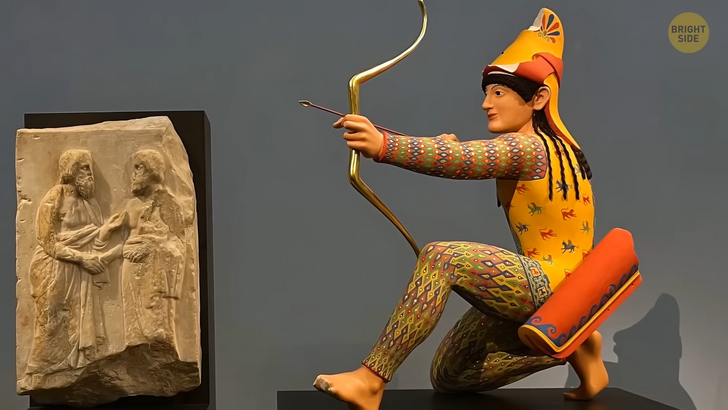

But remember that archaeologist we talked about? Brinkmann? Well, he has been collecting data on polychromy since the 1980s. At a certain point, he even began making colored replicas of such statues. The technology used is far from simple. To reconstitute these ancient works of art, Brinkmann makes a 3D plaster copy of them. Then, he paints them by hand with the help of his wife. To find out which colors were used in the original sculptures, Brinkmann uses UV light. Certain pigments glow under UV light, exposing traces that would otherwise be invisible.

Take this colorful archer as an example. Look at these colors! This piece is the reconstruction of a marble archer in the costume of a horseman. To accurately depict the archer, restorers had to research a lot about the history of the region where the art piece was originally found since colors have a cultural meaning. That, together with UV technology, allowed for the reconstruction you can now see.

It seems very far from the idea we have of what the Greeks would make, but this is supposed to look exactly like the original one! According to Brinkmann, we shouldn’t be so surprised that ancient western civilizations used bright colors to depict their realities. After all, the Romans and Greeks were heavily inspired by the works of art of Egyptian civilization, old Mesopotamia, and Asia.

For example, if you look at the famous Egyptian Sphinx, you might be led to believe that it always looked that way. But that wasn’t at all the case! Modern studies and virtual reconstructions of the monument show us that the monument was very colorful.

The body of the statue is believed to have been painted terracotta, while the regal headdress that circles the head is meant to have been gold and blue. All of these were considered important colors in Egyptian times, and it was only suitable to use them to depict a Pharaoh.