10 Times Good Intentions Became Embarrassing Memories That Still Haunt People

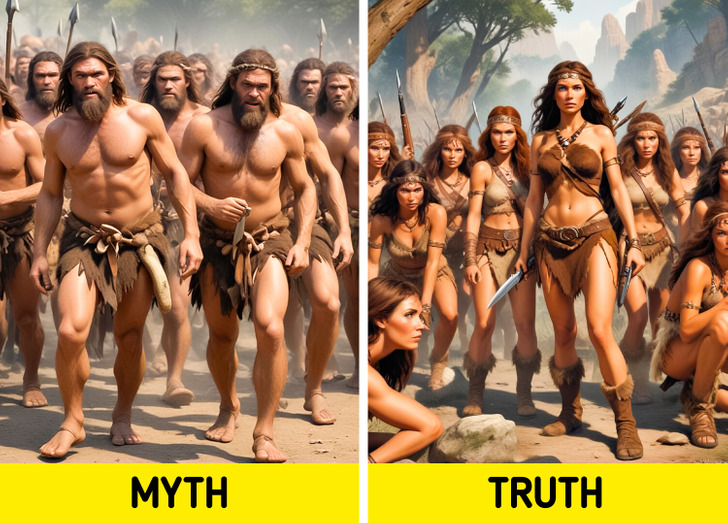

For decades, the prevailing theory in anthropology suggested a rigid division of labor in early human societies—men were the hunters, while women gathered and cared for children. This idea, often referred to as “Man the Hunter,” has been deeply ingrained in both academic circles and popular culture, shaping museum dioramas, textbooks, and even films. However, a growing body of evidence challenges this assumption, suggesting that women were active hunters alongside men in prehistoric societies.

The theory gained prominence in the 1960s, when anthropologists Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore published Man the Hunter, a collection of studies that argued hunting was the key driver of human evolution. The book framed men as the primary hunters, placing them at the center of societal development. It also assumed that women’s roles were restricted by pregnancy, lactation, and childcare responsibilities, making hunting impractical for them.

Yet, even within the studies included in Man the Hunter, there were cases of women actively participating in hunting—findings that were often dismissed or downplayed. For example, research on the Ainu people of northern Japan documented women hunting with the aid of dogs, but the focus remained on men as the dominant food providers.

Modern research in exercise science has shown that women are naturally suited for endurance activities. This finding is significant because one of the main prehistoric hunting techniques, known as persistence hunting, required running prey to exhaustion over long distances.

Here’s why women’s physiology supports endurance:

These traits align well with persistence hunting, in which humans pursued animals until they collapsed from exhaustion. Rather than being a limiting factor, female physiology appears to have been an asset in these hunting strategies.

Skeletal remains and burial sites also challenge the idea that only men hunted. For example, studies of Neanderthal remains reveal similar patterns of injuries and wear-and-tear on both male and female skeletons, indicating that they engaged in the same physically demanding tasks, including hunting.

One of the most compelling discoveries comes from a burial site in Peru dating back about 9,000 years. Researchers found the remains of a young woman buried with hunting tools—suggesting she had been a hunter rather than a gatherer. This site is not an isolated case; numerous other archaeological findings suggest that women played active roles in hunting throughout prehistory.

Beyond ancient findings, modern-day hunter-gatherer societies provide direct evidence that women hunt. The Agta people of the Philippines, for example, have women who hunt while pregnant and breastfeeding, with success rates similar to men. In other cultures across Africa, the Americas, and Australia, women actively participate in hunting alongside men.

A recent study reviewing ethnographic data from 63 foraging societies found that in nearly 80% of them, women engaged in hunting. This directly contradicts the idea that women were exclusively gatherers and caregivers.

The rigid gender roles assumed by the Man the Hunter theory are likely a product of more recent societal developments, such as agriculture. When early human groups transitioned to farming-based economies, labor became more specialized, and gender roles became more pronounced. Before this shift, survival depended on adaptability, and everyone needed to contribute to acquiring food.

The notion that hunting was a male-only activity is increasingly being dismantled by modern research in anthropology, physiology, and archaeology. Women were not merely passive gatherers but active participants in early hunting societies. As science continues to challenge outdated assumptions, our understanding of human history becomes richer, revealing a past where survival depended on cooperation rather than rigid gender roles.

Next time you picture prehistoric hunters, imagine a group of men and women working together—because that’s likely how it really was.

If history teaches us one thing, it's that our assumptions about gender have often been wrong. And it’s not just in ancient societies—our modern beliefs about children, especially toddlers, are filled with myths too. Want to know which ones? You might be surprised by what the research says.