10+ Celebrities Whose Style Changed Drastically After They Unleashed Their Inner Selves

The sky suddenly turns orange. All you can see as you look up are millions of butterflies. You just got lucky to witness the spectacular natural show: the annual migration of monarch butterflies. Every fall, as the days get shorter and the temperatures go down in the northeastern U.S. and Canada, these beautiful creatures leave their summer breeding grounds. They travel up to 3,000 miles to Mexico and never come back.

Their perfect overwintering ground is high in the mountains. Millions of monarch butterflies are safe there in the canopy of oyamel fir trees. Once the winter is over, it’s time for them to go back up north. They make a stopover around Texas to mate and lay eggs on milkweed plants. A few days later, these eggs turn into caterpillars that feed on the plant until they transform into grown-up butterflies.

Now it’s their turn to continue the journey up north until they find a new breeding ground. This way, generations keep changing en route, and it may take up to 5 of them to get to the final destination back in Canada. It’s a natural mystery how the butterflies traveling south live up to 8 months traveling with the air currents. The same species going back completes its life cycle in 5 to 7 weeks.

Scientists still don’t know why the monarchs migrate and how they find their way. It could be connected with the blooming of milkweed plants, their primary food source. They probably find their way around based on the position of the Sun.

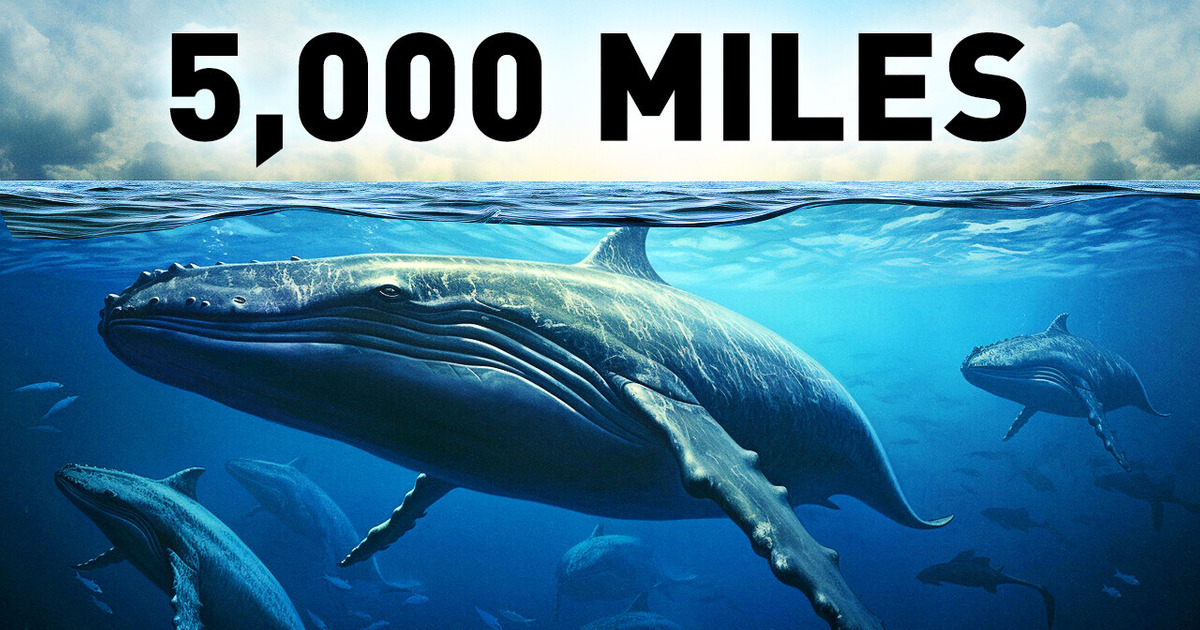

Humpback whales are real champions when it comes to migration and size among mammals. They cover a distance of up to 5,000 miles following their lunch. In the summer, they move towards the poles, to colder waters, where there’s plenty of krill and small fish. In the winter, they go south towards the equator’s tropical waters. They also travel to mate. They have specific locations where they gather to do it.

During the winter breeding season, you can hear male humpback whales “sing,” most likely to attract females or mark their territory. They produce a long series of calls and can repeat the same song for several hours. When the song changes, all singers that are currently migrating pick up the new tune. It’s amazing how they do it when the distance between groups can be over 3,000 miles!

Sea turtles migrate for more sentimental reasons. For hundreds of millions of years, these cute family guys return to the exact place where they were born to lay their eggs. They can cover up to thousands of miles, mostly when the seasons change and the waters are of a comfortable temperature.

It could take them years since some of them travel across the Pacific Ocean between Indonesia and the west coast of the United States and Canada, which is a total of 10,000 miles! But how do they find the exact spot they need if their parents can’t just send them a geotag?

Scientists have found out that they navigate using the invisible lines of the Earth’s magnetic field. It turns out that each part of the coastline has its unique magnetic characteristics. The turtles remember their and travel using their internal compass. The magnetic field changes slowly but surely, so they have to shift their nesting sites accordingly.

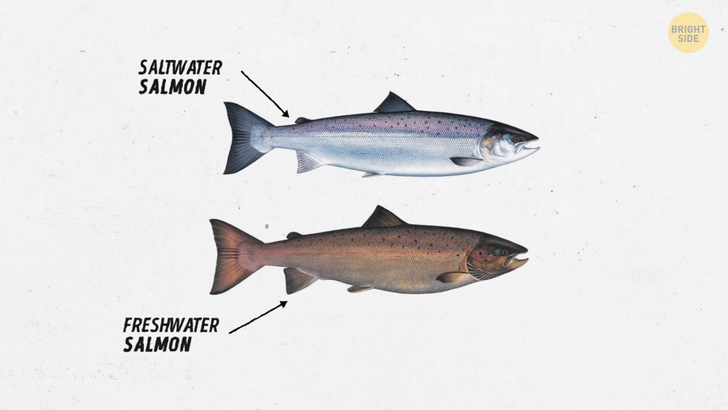

Salmon are born in freshwater streams and move to the ocean as juveniles. Atlantic salmon are brown and spotted as they cover hundreds of miles in freshwater and turn silvery in the ocean, where they travel for up to a thousand miles. Adult salmon stay in the ocean for one to five years feeding mostly on zooplankton. Then, it’s time for them to go back to fresh water to spawn. On their way back to the breeding grounds, they have to ascend thousands of feet against the current in mountain streams. This challenging journey is called a “salmon run.”

They set on this run because they know the stream they’re headed to will be good for spawning, and they’ll meet the right species to mate with. Young salmon remember the smell of their home stream and probably even take note of various points along the way to the ocean to find it again. Just like sea turtles, they use the Earth’s magnetic field as a compass for their travels. Pacific salmon and most male Atlantic salmon only live for a few weeks after spawning, and some female Atlantic salmon survive and migrate back to the ocean.

Caribou, better known as reindeer, are the champs when it comes to migration distance among land mammals. Every spring, they cover a distance of around 400 miles in Alaska, from their winter to their summer feeding grounds. Individuals cover up to 3,000 miles, but herd migration is way more spectacular. The largest herd [the Western Arctic Herd] has at least 260,000 members, and its migration territory covers an area larger than California.

Scientists put radio tracker collars on some herd members and take thousands of photos to count them all. This census is organized every three years in good weather conditions to see if the population figures are rising or falling and track their migration patterns.

Caribou grow through all this migration trouble to safely raise their newborn Youngs. They reach remote grounds where golden eagles, wolves, and grizzly bears won’t bother the youngsters during the first, most vulnerable days. Another good excuse to hit the road up north for them is to save themselves from mosquitoes, which would be a huge problem in the warmer months. Plus, they get fresh seasonal foods from the areas they stay in. Their migration helps fertilize the grounds they pass by, which means the tundra should thank them for regenerating and protecting its grasslands.

Wildebeest, also known as gnus, are relatives of antelopes and gazelles. They spend most of their lives in the Serengeti plains of southeastern Africa, grazing in the grassy savannas. Every year at the end of the rainy season, normally in May or June, millions of wildebeest head northwest in search of greener pastures and then back again.

This migration is so spectacular that it’s considered one of the seven wonders of the natural world. Sadly, not all wildebeest make it to their final destination, as they have to cross rivers full of giant crocodiles and pass by hungry lions and other predators.

If you look at dragonflies’ migration routes, you can call them real globetrotters. Scientists discovered one such route that spanned from India to the Maldives, Seychelles, Mozambique, Uganda, and back again, for at least 8,700 miles. It’s the longest insect migration we know of so far. It looks like they set on this epic journey when the temperature reaches a certain mark, and the days start to grow longer.

They seem to be following the rains as they start during the monsoon season in India and arrive for the rainy season in eastern and Southern Africa. One fragile insect cannot complete the whole trip, so it turns into a sort of relay race that includes four generations of dragonflies. Each generation plays its role in the journey.

Scientists can’t put radio trackers on dragonflies as they do with other animals because the insects are too small. So, to put together the migration route puzzle, they analyzed 21 years of data from volunteer citizen scientists and also wing samples from museums. Each of the samples had a chemical code that could roughly tell where the insect was from. This data helped the scientists understand how far this or that insect traveled as an adult.

Elephants are known to have traveled across Africa for centuries. They rely on their herd leaders’ memory when it comes to recalling the tricky migratory routes. This big elephant boss leads everyone else to sources of ripe food and water when the seasons change. They also migrate to avoid danger, which is mostly represented by humans.

Elephants have developed their own communicative methods to pass on information about prospective danger. They use chemical secretions, vibrations, gestures, and touch. Recently, many African countries have restored some of the oldest elephant migration routes. These big-eared guys usually avoid dangerous areas for generations, but once they know the route is safe, they start using it again.