11 Breakup Stories That Could Easily Be Movie Scripts

Listen to this: Neanderthal fiber technology. Nope, I’m not joking: the concept is real. In 2020, a team of scientists published a paper that redefined the way we saw our closest ancestors. A find in France changed archeology forever. And it wasn’t the first time something like this had happened.

But let me start from the beginning. Neanderthals. For a long time, they fit the image of the typical cavemen. If you are now thinking of someone like Fred Flintstone, you wouldn’t be much wrong. What was the reason behind this stereotype? When did we start believing that Neanderthals were not the brightest tools in the shed of evolution?

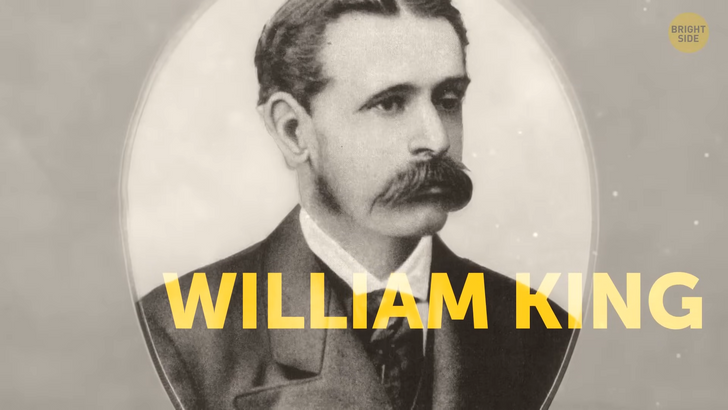

In comes William King, a 19th-century British geologist. He was the man who named the Neanderthals. Based on the bones King found, the scientist declared the species not intelligent. And this image stuck with the Neanderthals for centuries to come.

But a piece of string just a quarter of an inch long changed everything. A small, dry river valley [Abri du Maras] was the place of the great find. Archeologists unearthed a cord fragment next to a stone tool. Such twisted fibers could have been used for everything from making clothes to fishing nets.

In prehistory, this was some advanced tech and the Neanderthals seem to have mastered it. Scientists already knew that these early humans made tar from birchbark and that they produced shell beads. There is even evidence of Neanderthal art. They were definitely not primitive.

The string section and similar finds are changing the way we perceive our ancestors. The world of archeology is constantly changing. Take the Pyramids in Egypt, for example. Turns out, they weren’t really built by an army of people who the pharaoh made work until they passed out.

Herodotus, the famous Greek historian, was the man who started the confusion. He claimed [in 500 BCE] that 100,000 men took part in the construction of the Great Pyramid in Giza. He made no mention of who they were and why they were building the pyramids.

That’s how the myth started. Huge stone slabs pulled by humans, driven by a foreman with a whip. But Egyptologists would beg to differ. Those are the scientists who study Ancient Egypt’s culture. Fairly recently [1988], they uncovered a workers’ village that told a different tale. Yes, there was evidence of hard work on the workers’ bones.

But the construction industry is demanding even today. It took almost 6 years for 12,000 workers to complete the world’s tallest building [Burj Khalifa]. Back in Egypt, three times more workers finished the Great Pyramid in around two decades. An impressive feat of ancient engineering, wouldn’t you agree?

Superiors looked well after the Egyptians who build the pyramids. Their diet was rich in protein. They had medical care and they got paid properly. In fact, they lived better than the non-working population. And they lived with their families near the construction site. Archeologists know all this because they unearthed bakeries and dormitories with bread jars and other goodies. Looks like the pharaohs were OK employers after all, and the job market wasn’t that terrible.

They also kept detailed papyrus records of the build in hieroglyphs. You and I wouldn’t stand a chance of reading these letters that resemble images. Egyptologists had the same problem. For over a millennium [1,000 years], no one had used this type of font. And it’s not like there was an English-Ancient Egyptian dictionary you could open and find meanings of words. But all this changed in 1822.

A couple of decades before, the French found a broken slab of black granite. The stone contained one text in three scripts: ancient Greek, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Demotic. The last one was also the Egyptian language but in a simplified script. Scientists dated it back to 196 BCE.

The content is a religious proclamation. A French philologist and orientalist [Jean-François Champollion] was the first one to crack the code. You see, people haven’t forgotten ancient Greek letters. The Frenchman successfully matched the Greek letters with the ones in the Egyptian script. And voilà. We were finally able to read hieroglyphs.

The name of the piece of granite that made it all possible was the Rosetta Stone. The importance of its discovery went beyond archeology. The word [Rosetta Stone] even entered the English dictionary. It represents a discovery that helps people understand an enigma that has been puzzling them for a long time. There are similar games. A symbol is attached to a particular message. Then you have to decode the message by replacing the symbol with a corresponding letter. In a nutshell, this is what scientists did with the Rosetta Stone more than two centuries ago. But on a much, much bigger scale.

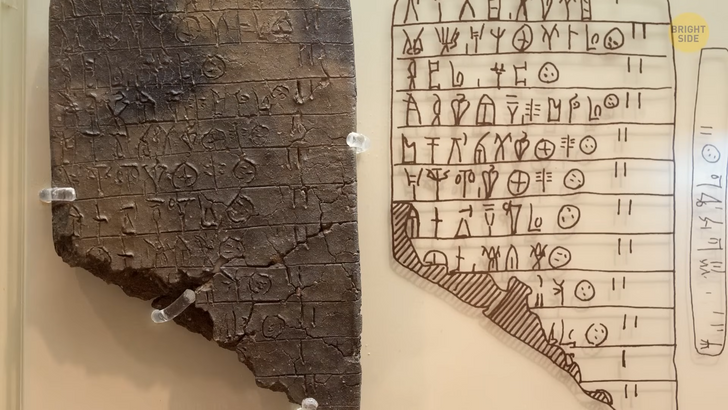

Do you know what is the oldest deciphered language in Europe? It has an unattractive name: Linear B. The script belongs to the Mycenaean Greek language. It predates the ancient Greek alphabet by several centuries. You can easily guess which script it is descended from [Linear A]. The people from Crete used Linear B more than a thousand years ago [1340 BCE — 1190 BCE]. During the Late Bronze Age, the Greek civilization that used the script vanished. There was no one who could read Linear B. And more importantly, no one knew it existed in the first place.

This was about to change during the first years of the 20th century. A British archeologist by the name of Sir Arthur Evans excavated a vast palace complex at Knossos [Crete, Greece]. This was the center of the Minoan culture that created the enigmatic script. The palace boasted some 1,300 rooms. They had colorful paintings of dolphins, griffins, and bulls. All of these captivated the archeologists’ imagination. But their biggest find was at first overlooked: thousands of slabs of baked clay. The fire that brought down the palace helped preserve the tablets.

It was impossible to read the slabs, though. They were written in an unknown language. The scientific community had to wait for another half a century before Michael Ventris cracked the code. He was an English architect and cryptographer. Ventris studied Greek and Latin.

While attending the famous archeologist’s lecture [Arthur Evans], the young man decided to solve the puzzle of Linear B once and for all. He managed to do so in 1952. One of Ventris’ most amazing discoveries was that the script was an archaic form of Greek. But cryptology still hasn’t solved the code of Linear A. This writing system will remain a mystery until a motivated young person like Michael Ventris comes along.

They wouldn’t have to be a professional archeologist. Basil Brown certainly wasn’t. Yet, in 1939 he discovered the richest early medieval tomb in Europe. This happened in Sutton Hoo, in the southeast of England. This wasn’t an ordinary tomb made out of stone. It was a full-sized ship, three times as long as а London double-decker bus [88.6 feet]. And that’s not all. Apart from its main purpose, the ship was full of riches. Deluxe hanging bowls, feasting vessels, golden dress accessories, and luxurious textiles were just some of the treasures found.

Archeologists were also amazed by the silverware from distant Byzantium. You probably know this city as Istanbul [Turkey]. Even in our age, it’s several days’ drive from Sutton Hoo. Just imagine how much time and money it cost to import a silver plate in the 7th century. That’s when the ship went down, according to archeologists. The English couldn’t have done it. At that time, there was no England. The people living in the British Isles at the time were the Anglo-Saxons.

Perhaps the ship from the grassy mounds in Suffolk belonged to one of their kings? We will never know. The local acidic soil did away with any possible evidence. Or no one laid there in the first place. It could have been a cenotaph, which is a monument constructed to honor an important person. The archeologists still don’t have a definite answer.

But what they have found at Sutton Hoo shed light on the Dark Ages. Before the discovery of the ship, they knew little about what had been going on in Britain after the Romans left. Now, the image of the early Anglo-Saxon society was much clearer. Perhaps the English soil will be the site of the next great breakthrough in archeology.