Why Europe Doesn’t Build Skyscrapers Like US or Asia

Most of Europe’s skyscrapers are concentrated in 5 cities. But even combined, all these places have fewer skyscrapers than New York City alone! For a building to be considered a modern skyscraper, it has to be about 490 ft high, which means it should have at least 40 to 50 stories. A story is simply one floor of a building with an average of 14 feet from floor to ceiling.

If you had visited the US just before the 1870s, you’d have found only one skyscraper. The Home Insurance Building in Chicago was the world’s first high-rise building, with 10 floors. Wow! North America started to construct more and more high-rise buildings. It happened because cities were getting too populated. Every piece of land was too valuable.

New York’s skyline is so famous you’d probably recognize it even if you’ve never been to this city before. It’s the same for Paris. But could you imagine the Eiffel Tower surrounded or even blocked by skyscrapers? It would surely lose some of its magic! La Défense district is where you’ll find skyscrapers in Paris. This way, they don’t interfere with the romantic and touristic scenery of the city.

In London, things are done a bit differently. Some of its skyscrapers have unusual shapes. One of such constructions is the Gherkin. (If you get stuck in this building, you’d really be in a pickle).

Another interestingly-shaped skyscraper is the Shard. There’s one more, nicknamed the Cheesegrater. These are not their official names, of course. But they do make sense if you look at the shape of these buildings.

But it’s not some random architectural concept. The reason the skyscrapers are shaped like this is not to obscure Saint Paul’s Cathedral. (By the way, the top of this monumental construction is visible even from King Henry VIII’s Mound. And that’s a great distance away!) Anyway, there are also other sights, like the Tower of London and the Palace of Westminster. They have their own viewpoints. So, not to ruin London’s skyline, it’s not allowed to build anything that would block these monuments.

Most European cities already existed when the US started to build its first skyscrapers. That’s why they didn’t have much space to fit in giant buildings. Evenly zoned cities were the result of their steady growth throughout the years. For example, in Lisbon, there’s a viewpoint in Eduardo VII [Edwardo cetimo] park.

From that place, you can see all the park and the river. If suddenly there was a bunch of 490-ft-tall buildings standing around, this gorgeous view would be totally ruined. You wouldn’t see the iconic avenue. And forget the river. Instead, there are buildings.

Like Lisbon, many other cities in Europe don’t want skyscrapers to spoil their cultural heritage. Take Germany. Most of their skyscrapers are in Frankfurt. In other cities, they’d rather protect and restore the buildings that are already standing. And even if, let’s say, Berlin wanted to home some skyscrapers, it wouldn’t be able to do it in any case. Its soil just wouldn’t allow it. Put a skyscraper there, and it’ll sink! Constructing a foundation for a very tall building in Berlin would mean investing a lot of money. The soil’s too sandy and soft.

But what if you ignored all the cultural heritage and still decided to fill a European city, like Prague, with skyscrapers? First, you’d have to demolish a lot of what already exists there. This would lead to an angry crowd of people complaining that the city they know and love is gone.

Brussels has experienced this to a certain extent. There’s even a term for this phenomenon — Brusselization. Put simply, it means not caring where you place new high-rise buildings. Here is fine. Oh, sprout one over there too. Hey we could call them Brussel Sprouts. Or not.

But in most cases, city authorities don’t want new constructions to change the historical appearance of the place. Some large European cities might even follow France’s example and choose a separate district — a place just for skyscrapers.

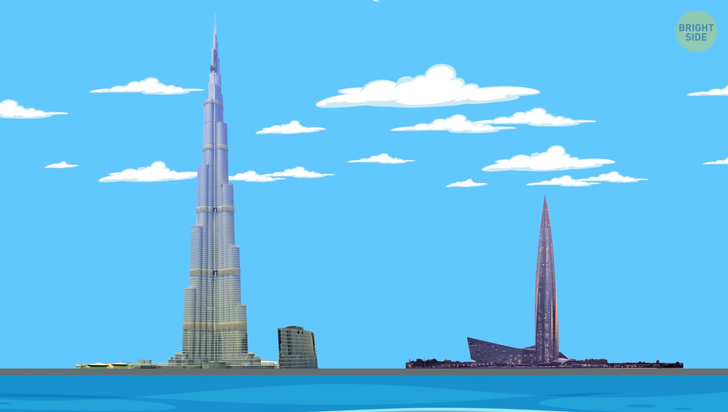

Well, the question is if skyscrapers are so tall, why don’t they get knocked over by wind? Their structure, from the very foundation to the highest point of the building, is the answer. Take the Burj Khalifa. Please.

The soil where the skyscraper is built isn’t ideal. So, beneath the 110,000-ton concrete foundation of this massive construction, there are 192 piles, driven to a depth of more than 160 ft. Thanks to the friction between concrete and soil, these piles don’t move at all, creating a solid foundation.

But most skyscrapers are still built on bedrock because it barely shifts. Their frames are made of steel. If you looked at a skyscraper without its external structure (whew!), all you’d see would be a bunch of steel beams.

The taller the building, the more the winds affect it. Taming them is one of the biggest challenges skyscrapers have to tackle. Imagine you’re on one of the top floors of a skyscraper. Suddenly, a strong gust of wind hits the building. The entire construction starts wobbling, and you can feel it even inside. You might even get knocked over if you don’t grab onto something.

To avoid such a situation, most skyscrapers have a pendulum-like structure inside. It absorbs some of the wind’s force. This thing is called a tuned mass damper. The mechanism acts as a counterweight. When a skyscraper gets hit by the wind, it’s the tuned mass damper that moves instead of the building.

Some high-rise constructions don’t need this “pendulum.” The Shard, for example, deals with the wind with the help of its tapered shape. And Shanghai Tower uses its 120-degree twist. Both skyscrapers have incredibly smart structures. That’s why they don’t get too wobbly when the wind hits them. The Shard doesn’t have a tuned mass damper whatsoever. And the one in Shanghai Tower only serves as a tourist attraction.

Before a building’s design is finalized, it normally undergoes a wind tunnel test. A model city is built and tested with this new super-tall addition. When experts turn “the wind” on, it simulates real-life conditions. Let’s say, the model skyscraper breaks under the wind’s pressure during the test. Then the chances are it’s going to tumble over in real life too.

Winds up there can be so strong that things like wind turbines have become a thing. The Bahrain World Center has 3 of them, right in the middle of the building. But there are some others: Strata SE1, for example, has wind turbines at the top.

There’s a phenomenon called the “downdraught effect.” It’s accelerated winds near skyscrapers. When a powerful gust of wind hits a high-rise building, it gets pushed upward, around the sides of the construction, and down toward the street. That’s why if you’re passing by a particularly tall building on a windy day, you might have to force your way around.

But let’s say, several square-cornered skyscrapers are built next to each other. Then they’re likely to channel the wind through the streets. This can create mini-hurricanes on especially windy days. A study once examined 100 tallest buildings that were about to be dismantled by their owners. It turned out most of them had an average lifespan of a mere 42 years!

But some of them can last much longer. For example, the Temple Court Building is still standing to this day. At 150 ft, it’s a bit smaller than others. But it’s already seen over 100 winters throughout its life!

The first thing that comes to mind when you think of getting rid of a building is dust, debris, and deafening noise. But things aren’t quite as dramatic as that for most skyscrapers. When you want it gone, you take it apart, bit by bit. This process starts from the top and goes all the way down to the bottom. Voilà — the building is slowly disappearing in front of your eyes. Abracadabra!

Comments

Related Reads

"Looks Older Than His Age," Madonna’s Son, Rocco, Leaves Fans Stunned in New Photo

9 Unexpected Things That Show a Marriage Won’t Last Long

My DIL Insulted Me Being Unaware I Was Supporting Their Family, My Revenge Made Her Turn Pale

“1000-lb Sisters” Star Stuns in a Swimsuit After Dramatic Transformation and Looks Unrecognizable

“Ruined Her Face”, Nicole Kidman’s Met Gala Look Sparks Concern

11 Breakup Stories That Could Easily Be Movie Scripts

12 People Who Were Masters at Hiding Their True Intentions

My Husband Has to Meet 3 Conditions Before I Get Pregnant — He Refused the Last One

20 True Stories That Show How Infidelity Divides Life Into “Before” and “After”

12 People Who Uncovered a Dark Reality Many Years Later

My Husband’s Dark Secret Was Revealed During a Family Dinner, He Kept It From Me for 20 Years

My Granddaughter Made Me Leave Her Wedding Because of My “Embarrassing” Look