15 Real-Life Stories That Prove Kindness Is Part of Being Human

China’s Yutu-2 is a robotic mission to the dark side of the Moon launched on December 7, 2018. On January 3, 2019, it completes the first-ever soft landing on the lunar far side. It lands in the Von Karman crater, not far from the Moon’s South Pole. Scientists are interested in this area. Cold, permanently shadowed craters at the poles contain water ice.

These ice patches are uneven and are likely to be ancient. In the south, most of the water ice is concentrated in craters. And at the North Pole, it’s spread more sparsely. In any case, this ice can be used once a long-term manned mission lands on the Moon.

Anyway, several days after Yutu-2 lands, it closes down its operating systems and hibernates through its first lunar night. It “wakes up” on January 29, 2019. All its tools operate normally. The rover travels 390 ft [119 m] during its first full lunar day.

One lunar day lasts for about 14 days, and a lunar night has the same duration. Moving and exploring during the day and switching off during the night becomes the rover’s routine.

It’s the 8th lunar day when Yutu-2 stumbles across something incredible. This discovery makes the scientists put off all other plans for the mission. They focus on figuring out what the strange material found by the rover is.

In the beginning, this lunar day is no different from any other. It begins on July 25 [, 2019] when the rover starts making its way through an area pockmarked with tiny impact craters. Yutu-2 is helped and monitored by the driver team from the Beijing Aerospace Control Center.

On July 28, [2019] the team is preparing to shut the rover down for a “midday” nap. The sun is high in the sky. It means there are high levels of radiation and scorching temperatures that can damage the machine. Before powering Yutu-2 down, the scientists are looking through the pictures taken by the rover’s main camera.

That’s when they spot it — a small crater filled with something that looks shockingly different from the surrounding landscape. Unable to identify the gel-like substance, the team orders the rover to check this bizarre finding.

Yutu-2 cautiously nears the crater to examine the weirdly colored stuff. The machine uses special equipment that detects the light reflected off the substance. It’s supposed to help the researchers to understand the structure of the material. Unfortunately, the nature of the unusually colored finding has remained a mystery for over a year.

No wonder that both the finding and the fact that initially, there were no images of the enigmatic stuff sparked curiosity all over the world. The only available description of the substance was that it looked like a randomly colored, shiny gel — something that’s rather odd for the dusty, arid surface of the Moon.

But finally, the mystery seems to have been solved! The researchers have analyzed the information received from the rover’s equipment. As expected, the substance turned out to be made up of rock — greenish and glistening breccia, in a sample no larger than 20 [in (51 cm)] by 6 [in (15 cm)] inches. It’s kinda like a geologic version of Jell-O salad with fruit inside. If you melt it down, it’ll look glassy.

Breccia consists of sharp stones joined together by a chalky substance. The sample found on the far side of the Moon is made up of a mix of different minerals. The main is a type of silicate that’s one of the most common components in both the Moon and Earth’s crust.

The piece also contains some glass, which means it could have formed during a volcanic eruption. But volcanic activity on the Moon stopped more than 3 billion years ago. That’s why the researchers are almost sure it’s unlikely to be the source of the unusual finding.

The material could have been created by a massive asteroid, comet, or meteorite that once hit the Moon. During the collision, the pressure and temperature were so high that huge amounts of rock instantly melted.

Some pieces cooled down rapidly enough to form glass. The rest gathered at the center of the impact crater and grew colder more slowly, forming a new rock.

The substance was likely not formed in the Von Karman crater, but in the nearby Finsen [crater] and Alder craters. The hollow where the rover made its finding was just 7 ft [(2 m)] feet across. Whatever left it had to be no wider than an inch [1 in (2.5 cm)]. But then, it would be too small to create such a large piece of breccia.

It’s interesting that the material is similar to the samples collected by the astronauts from NASA’s Apollo missions. One of those samples was made of dark broken shards of minerals glued together.

It also contained some black, shiny glass. It’s not clear, though, whether it’s the same as the stuff discovered by Yutu-2. When the rover took photos and made its measurements, it was rather dark in the area. The quality of the images isn’t that great.

The experts also explain that the mission is examining a previously unexplored area of the Moon. That’s why they don’t have any samples from that region to compare them with the greenish, shiny substance Yutu-2 found.

But if their guesses turn out to be true, then the far side of the Moon might have more in common with the Earth-facing one than we used to think.

But what’s so special about this “dark side” of Earth’s natural satellite and why can’t we see it?

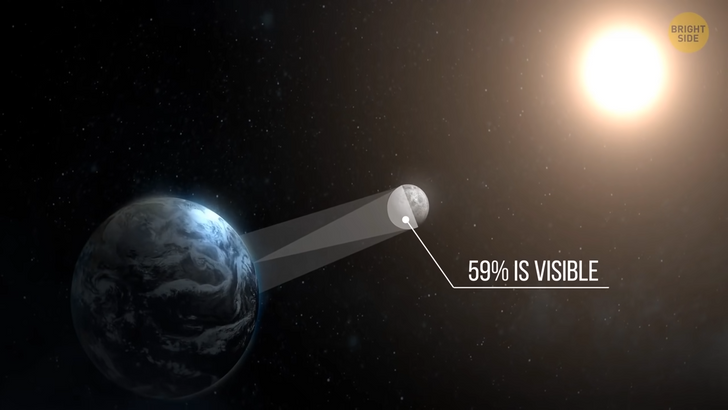

It’s all because of the phenomenon known as Tidal Locking. Earth’s only natural satellite rotates around its axis once in 27 days. It’s the same amount of time it needs to go round our planet .

That’s why you always see the same face. To be precise, 59% of the Moon’s surface is visible to people. It means that you can catch glimpses of the satellite’s far side at some times of the year.

The Moon’s side we can’t see is quite different from the one facing Earth. It doesn’t have dark spots that are visible at night. Those are lunar basaltic plains called Lunar Maria.

They were created by ancient volcanic eruptions. Those happened about 3-4 billion years ago. Instead of plains, the far surface of the Moon has countless craters and tall mountains.

One of the ideas about such a striking difference between the two sides is based on the collision theory. It claims that billions of years ago, Earth collided with another planet or some other massive space body.

After that, the debris from this collision crashed with something that would later form our Moon. That’s why the satellite’s landscapes differ so greatly.

A more recent theory suggests that the Earth-facing part of the Moon is warmer because of the heat radiated by our planet. During the period of volcanic eruptions, it was cooler on the farther side. That’s why the minerals there became solid faster.

They formed a protective layer shielding the Moon’s insides against the meteorites. But each impact left an impressive crater. At the same time, a much softer crust on the front-facing side of the Moon spewed lava every time a meteorite hit it. After this lava cooled down, it covered the impact craters.

Even though the far side is often called dark, both sides get almost the same amount of sunlight. The side we see looks a bit brighter because of the glow coming from Earth.

There are two reasons why people are interested in exploring the far side of the Moon. After leaving our planet, many radio waves get blocked by Earth’s natural satellite.

If astronomers could build their radio and optical telescopes on the “dark side,” they would get much more data. There would be no problems with any kind of interference.

The telescopes would also be shielded from the glare of daylight coming from our planet. If telescopes were set up inside craters, they would also be protected from solar radiation. Astronomers would be able to get an incredibly clear view of the far regions of the Universe.

Plus, scientists believe there are great amounts of helium-3 on the opposite side of the Moon. Earth is protected from solar winds that carry this gas by its magnetic field. But our natural satellite doesn’t have such a shield.

That’s why experts believe the Moon can be a perfect place for helium-3 mining. This rare element can be later used as the fuel for fusion reactors.