13 Parents Who Chose Their Kids Even When It Cost Them Everything

When we look at creatures in the animal kingdom, we often have the following thought: if they have similar traits, they must be related somehow. Zebras, horses, and camels must have some common ancestor. The same goes for dogs and jackals: somewhere back in their lineage, they must have some common great-great-great grand...wolf, right?

Well, the way evolution works in nature is way more complex. Take, for instance, convergent evolution, which is when different creatures evolve independently of each other but end up having similar traits.

We only need to look at sharks and dolphins to see how this works. At first glance, they look very similar: aquatic creatures, with some species having roughly the same size. But turns out they are mostly unrelated.

Sharks are fish, they reproduce by laying eggs and evolved to have the ability to sniff out blood in the water to feed themselves. Dolphins on the other hand are mammals. They are friendly and have a way more interesting social life. Take bottlenose dolphins, which have their own special whistles, that they use similar to how humans use their names.

Not only do they develop this type of whistle to introduce themselves to other dolphins, but they can also learn other such “names” so they can better communicate with each other. Sure, sharks and dolphins did have a common ancestor, but this one lived in the sea almost 300 million years ago. It’s safe to say dolphins and sharks aren’t even cousins these days.

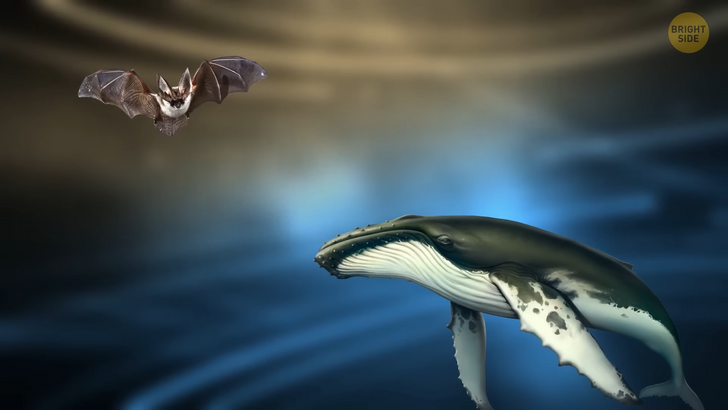

Another more shocking example of convergent evolution is that of whales and bats. Most of the creatures we can name on the top of our heads use light — and sight — to understand the world around them. But there is a specific set of creatures that relies on sound to paint them a picture of their environment.

What they do is they emit a sound, which bounces back to them depending on the objects it hits. This ability is called echolocation. Animals that have this feature emit sounds at frequencies above human hearing, called ultrasound. Those sound waves bounce off objects while they move around, allowing them to figure out where they are in a certain space.

Echolocation is mostly used by toothed whales and by some species of bats. What’s similar in both of these animals is that they need to hunt in the darkness. Despite this, they echolocate in very different ways. Bats, for instance, use their throats to generate ultrasound from their mouth or nose. Then they proceed to listen for changes in the echoes. Their echolocation is so finely tuned, that they can distinguish targets less than 0.01 inches apart. Even if their target is moving!

Whales on the other hand echolocate by pushing air through their nasal cavity. This movement creates vibrations in a special fatty organ called the ’melon’. This organ focuses and modulates the sound, which then passes into the water around the whale. Whales then pick up the reflections of these sounds through their lower jaw and around the ears.

Another striking example of evolutionary convergence is that of Ichthyosaurs and Dolphins. Visually, the Mesozoic ‘fish lizards’ named Ichthyosaurs seem very similar to modern dolphins. But the friendly mammals are much more related to giraffes and camels than the ancient creatures.

Despite being 200 million years apart, they do share some common traits which mislead people into thinking they belong to the same species. But that’s mostly because they lived in the same environment. They both evolved to feature dorsal fins, which keep them balanced while swimming.

Now let’s look at phytosaurs and crocodiles. The first ones were reptiles that roamed the Earth back in the Triassic Period. They weren’t dinosaurs, but they lived at the same time as the first dinosaurs did.

Even though they look very similar, the first crocodiles popped up more than 70 million years later, in the Cretaceous Period. These two even fooled paleontologists at first. They initially assumed that phytosaurs were the ancestors of crocodiles.

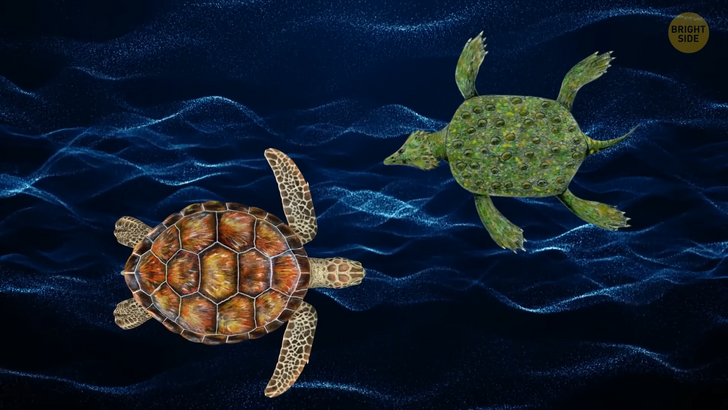

Placodonts and turtles look similar, too. Placodonts however appeared about the same time as the dinosaurs did, somewhere around 235 million years ago. Like modern turtles, they lived in marine environments, but they were surrounded by predators. So, they evolved to have really strong shells to protect themselves.

Turtles, however, made it to the scene around 100 million years later. Even modern cats have an ancient look-alike. They were called the sparassodonts, but they were carnivores and marsupials. They used to live in the South American area and resembled the saber-toothed tiger, which is now extinct.

Speaking of saber-toothed tigers, how about one that’s also related to the kangaroo? Yeah, this creature used to freely roam the Earth around 3 million years ago. The Thylacosmilus may have looked like a feline, but was a marsupial, meaning it had a pouch of skin in which it carried its pups for a certain period after their birth.

Like kangaroos and opossums do today. It’s difficult to estimate what they looked like since a full skeleton has never been found, but we do know they weighed between 180 and 260 lb.

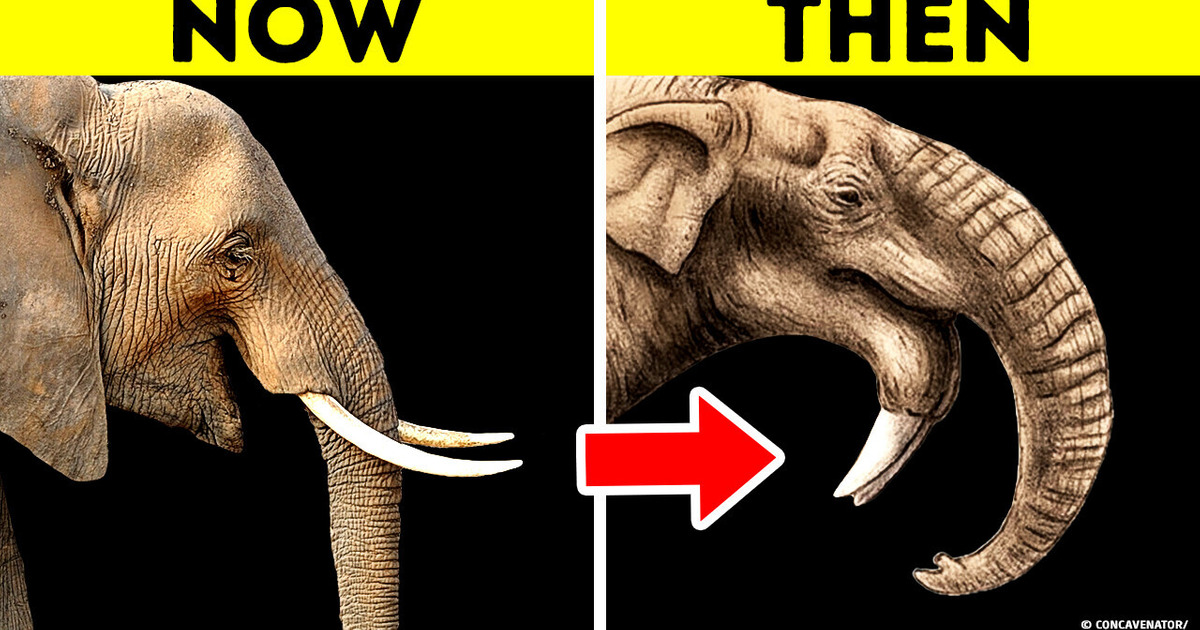

When we picture a present-day elephant, we always imagine them with their tusks protruding upwards. Well, that’s not how their ancestors did it. About 20 million years ago there lived a prehistoric elephant-like creature named Deinotherium. It did, however, have both tusks curving down from their jaw. As with many other prehistoric creatures, we don’t know why they had this feature the other way around, but one theory suggests they used them as anchors. By securing themselves to riverbanks, they were able to safely sleep without drifting off.

The last thylacine passed away in the early twentieth century. Their extinction was one of the most tragic natural events in modern times. For the last 2,000 years, they have been known to live only on the island of Tasmania. Despite the name, they looked more like foxes than felines. However, thylacines were marsupials rather than placental mammals like foxes.

The Toolache Wallaby was one of the most beautiful and majestic creatures ever to have lived. It used to be found in Australia and New Zealand. They were very similar to the kangaroos and featured fine fur with shifting bands of darker and lighter gray across their backs. Surprisingly, they were dubbed monkey-face, but they had no connection whatsoever to modern monkeys — apart from both being mammals.

What made them so special was the way they moved around. Their standard movement consisted of two short hops, followed by a long one. After that, the wallaby would simply stare into the sky. Don’t be fooled though, the Toolache Wallaby was extremely rapid. Females were generally taller than males, and they appear to have been quite sociable animals, at times being particularly fond of a certain location. They were also nocturnal.

Hyracodonts and horses share a lot of similar features. But Hyracodonts used to exist in the Eocene and Oligocene periods, and they went extinct around 23 million years ago. In their whole group, they featured very diverse species and came in many different sizes: from the small, pony-like to the colossal paraceratherium, which is one of the largest land-living mammals ever to exist. Modern horses however appeared around 2 million years ago.

Let’s do a little experiment together: start by stretching your arm out. If you were to draw a line from your fingertips to your shoulder, it would measure around 28 inches. Now try to picture an insect with a wingspan this big. Hold on a minute, you won’t need a large can of bug spray, don’t worry, they’re extinct. But the gigantic Meganeuropsis did live around 250 to 300 million years ago.

However, they most likely resembled the present-day dragonflies, despite not being technically related. Scientists figured out that they were not true dragonflies because of differences in the shape of their wing veins. Scientists still don’t know why these bugs turned out so big.

Some believe insects are limited in size because of the small quantity of oxygen that they’re able to take in. In the times when these insects roamed the Earth, the levels of oxygen in our atmosphere were much higher, so that might be one explanation. Other specialists think that they got so big because there wasn’t any other predator large enough to pick them up from the ground.