Brilliance and so beautiful The essence of the Solar System of which you as NASA do comprehend our Solar System is ETERNITY.I am Aquarius Seminole Cherokee and British As known Aquarius Pluto transit Aquarius this is fact and truth.

Uranus and Neptune May Have Oceans 5,000 Miles Deep, Science Says

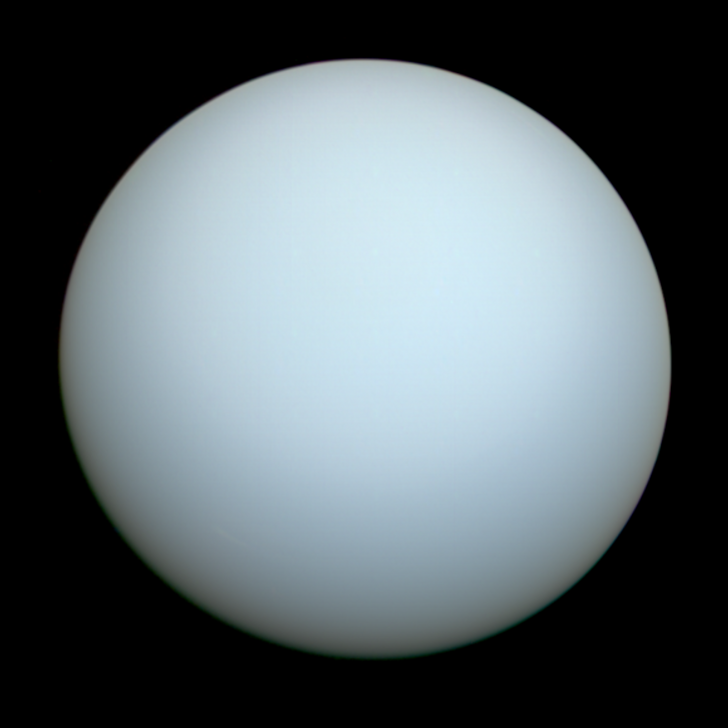

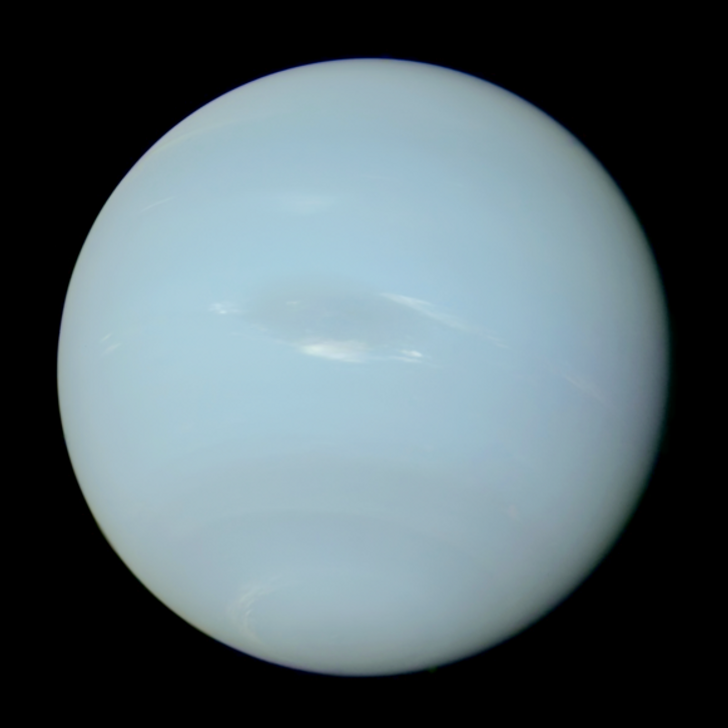

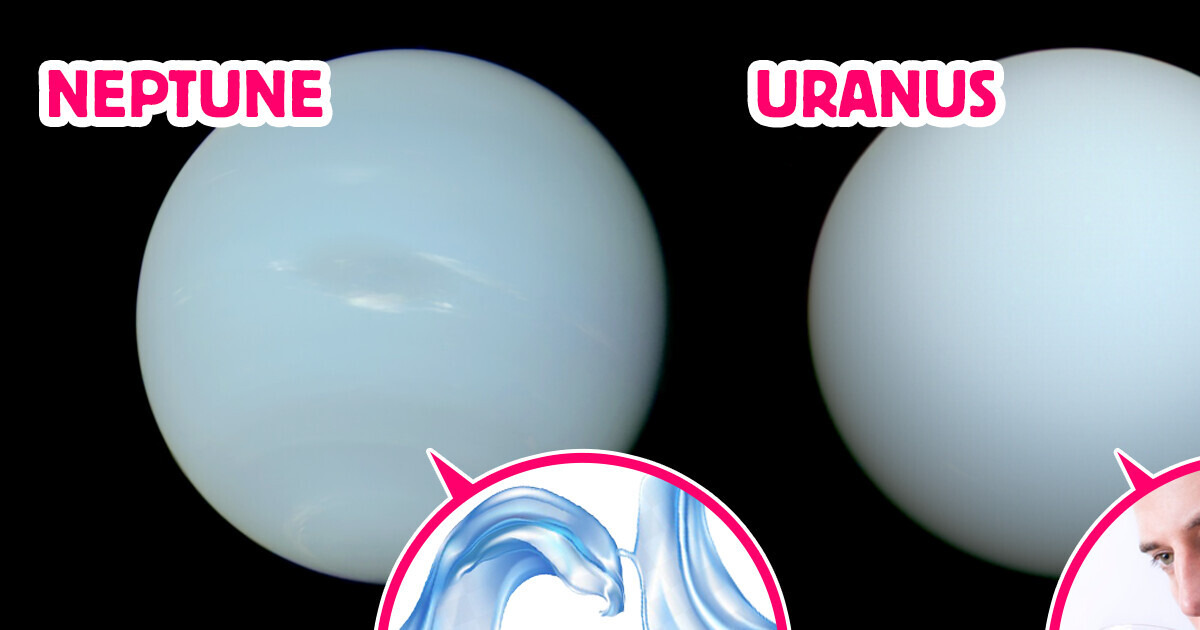

If you ask people which planet in the solar system they like the most (besides Earth, or maybe they won’t even mention Earth at all), very few will pick Uranus or Neptune. These outer planets don’t look all that exciting. The fact that they both have a similar greenish-blue color hasn’t changed that. But now, a new theory about what’s inside these planets could make them a lot more interesting.

And the best part? It involves water — a lot of it.

Since gas giants like Uranus and Neptune are the most common type of planet in the Milky Way, this discovery could be a big deal when it comes to finding life elsewhere in the universe.

A new study published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests something fascinating about Uranus and Neptune. Using computer simulations, scientists propose that beneath their thick, bluish hydrogen-and-helium atmospheres, these planets may have layers that don’t mix, kind of like oil and water.

For years, scientists have thought that the ice giants might have diamond rain inside them.

But this new theory suggests something different: a deep ocean of water lies just beneath the clouds in their atmospheres. Below that, there could be a layer of hydrocarbons, a dense fluid made of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen. These layers are about 5,000 miles (8,000 kilometers) thick.

What’s interesting is that the layers don’t mix because the temperature and pressure inside these planets push hydrogen out of methane and ammonia, making it hard for particles to mix, unlike on Earth. This might explain why Uranus and Neptune have magnetic fields that don’t follow the typical pattern seen on Earth. NASA’s Voyager 2 probe, which flew by the planets in 1986 and 1989, discovered this unusual magnetic behavior.

No spacecraft has visited these planets since then.

Burkhard Militzer, a professor at UC Berkeley, says this new theory could be key to understanding why Uranus and Neptune’s magnetic fields are so different from Earth’s, Jupiter’s, and Saturn’s. He compares the layers inside the planets to oil and water, with the “oil” (hydrocarbons) sinking below the water.

Militzer developed the theory using machine learning to simulate how atoms behave when heated and compressed. He says that years ago, he couldn’t have predicted this separation, but now it’s happening in his models.

The gravity fields predicted by Militzer’s model match what NASA’s Voyager 2 measured almost 40 years ago, adding support to this new idea.

NASA has plans for a mission to Uranus, which could help confirm the theory.

A proposed mission would send a spacecraft to orbit Uranus, but it would need a special Doppler imager to measure the planet’s vibrations since a layered planet would vibrate at different frequencies. A mission to Uranus could also study the planet’s moons, some of which may have oceans. One of its moons, Miranda, may even have an ocean beneath its icy surface, which would make it another possible candidate for life, like Europa at Jupiter and Enceladus at Saturn.

However, for the mission to work, NASA would need to launch by 2034 to take advantage of a rare planetary alignment, which would allow a gravity-assist slingshot around Jupiter to shorten the journey to Uranus to just 11 years.

Comments

Related Reads

14+ Sons Whose Handsomeness Can Outshine Their Celebrity Dads

14 People Who Had to Stop and Rethink Their Family’s Whole Past

10+ True Events That Get Creepier the More You Read

«You Ain’t Got the Body to Pull It Off», Stunning Selena Gomez Deemed Too Big For Her Tight Dress

16 Real-Life Stories That Prove Kindness Is the Strongest Defense Against Hate

16 Moments That Show Kindness and Empathy Stay Warm in a Cold World

10 Moments That Prove Quiet Kindness Keeps the World Standing

11 People Who Found Happiness in the Last Place They Looked—Thanks to a Stranger’s Quiet Act of Kindness

My MIL From Hell Said I Wasn’t “Family”, So I Made Her Regret It

I Refused to Let My Boss Track My Every Move—I Don’t Need an “Ankle Monitor”

15 Moments That Prove Kindness and Mercy Are Quietly Saving the World

10 Moments of Superhuman Strength That Feel Like Winning the Olympic Games