We Used AI to See How 10 Historical Figures Would Look Nowadays

With the help of modern technology, researchers continue to uncover fascinating details hidden within historical paintings. Some artworks reveal concealed images beneath the surface, while others contain secret characters that art historians are just now discovering. Yet, even with advanced tools, certain mysteries remain unsolved. We took a deep dive into these intriguing findings that might just change the way you see some of the world’s most famous paintings.

One of Claude Monet’s most well-known paintings appears to feature multiple women, but in reality, they were all modeled by the same person, his future wife, 19-year-old Camille Doncieux. While critics were initially unimpressed, the artwork later gained recognition for its unique approach.

The reason behind Monet’s choice to use only one model remains a mystery. Some believe it was a romantic gesture, a way for him to showcase his deep admiration for Camille. Others think he was experimenting with light and color, studying how they transform the appearance of the same face and figure in different settings.

In 1883, Pierre-Auguste Renoir painted the portrait of Valentine Clapisson, creating a striking contrast between her dark blue dress, cream gloves, and the pale abstract background. However, recent research has revealed that the painting originally looked very different.

Using Raman spectroscopy, a team of chemists detected traces of faded pigments, allowing them to reconstruct the painting’s true colors. Renoir had actually chosen a vivid red background, accented with blue and pink brushstrokes. Unfortunately, the natural pigments he used were highly sensitive to light and faded over time. Though more durable dyes existed, many artists, including Renoir, preferred traditional materials, even knowing that their vibrancy wouldn’t last forever.

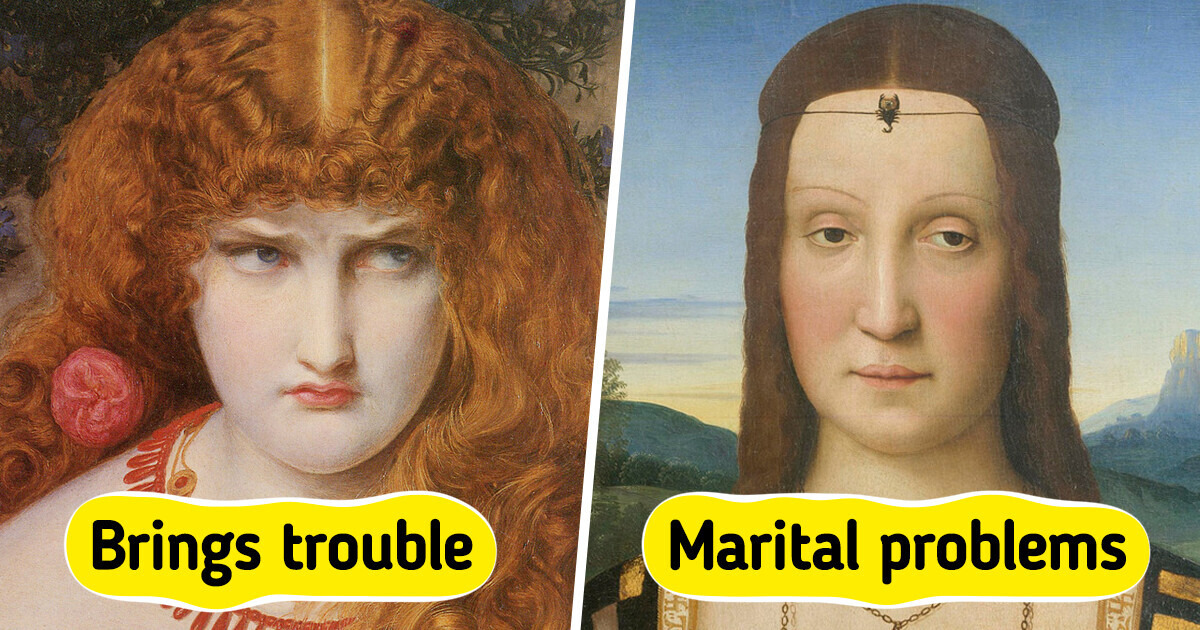

The Pre-Raphaelites, English artists from the second half of the 19th century, often depicted mythical characters. Their vivid and detailed paintings were filled with symbolism, so it could take a lot of time for a viewer to decipher the embedded message.

It is no coincidence that Frederick Sandys painted Helen of Troy wearing gold and coral necklaces. Corals were associated with both divinity and expense. Therefore, the heroine is depicted as the most beautiful woman in the world, whose appearance has brought many troubles.

Duchess Gonzaga was one of the most iconic figures in the cultural life of the time. She was called a personification of grace, so it is not surprising that she was painted by the famous Raphael Santi. The unusual pendant that adorns the woman’s forehead hints at her marital problems. Elizabeth’s husband was infertile, and she wanted to have children, so the woman wore a jewel in the shape of a scorpion that was linked to fertility.

For years, no one suspected that Joshua Reynolds’ painting, depicting a scene from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, contained a hidden figure. It wasn’t until a recent restoration, where layers of varnish were carefully removed, that experts uncovered a demon lurking near the Cardinal’s bedside.

The demon seen in Caroline Watson’s engraving may not have vanished by accident. When Joshua Reynolds included the eerie figure in his painting, he took Shakespeare’s words quite literally, but his artistic choice wasn’t well received. Critics of the time dismissed it as childish and in poor taste, openly criticizing the decision.

Some even pushed for the demon’s removal, though Reynolds fought to keep it. Over the years, the figure slowly faded into the shadows—not just due to age, but because the painting was altered multiple times. Researchers discovered that it had been painted over and buried under six layers of varnish, likely in an effort to erase what was once seen as an unnecessary addition.

When Irises by Van Gogh was first unveiled, viewers were captivated by its vibrancy and energy. The painting’s rich colors and airy composition left a lasting impression, with one critic even praising Van Gogh’s ability to capture the delicate beauty of flowers.

Even today, the artwork continues to amaze, but what we see now isn’t quite the same as what his contemporaries did. Recent research has revealed that the irises were originally a deep purple. Van Gogh achieved this shade by blending blue and red pigments, but over time, the red faded due to its sensitivity to light. As a result, what was once a striking purple has gradually transformed into the blue we recognize today.

The painting Madonna della Vittoria, completed in 1496, contains a fascinating detail that has puzzled researchers. At a time when direct trade routes between Europe and Southeast Asia didn’t yet exist, the artwork features a bird in the upper left corner that closely resembles a yellow-crested cockatoo—a species native to certain Indonesian islands and now considered endangered. Given how naturally the bird is depicted, it was likely painted from life, rather than imagined.

This raised an intriguing question: how did the cockatoo make its way to Europe? Experts believe it may have traveled along the Silk Road, a journey that could have taken years. However, since these parrots have a lifespan of up to 60 years, the long trip was entirely possible. Another theory suggests the bird could have arrived via India, making its way westward through trade. No matter how it got there, its incredible journey could have made for quite a story.

Seurat painted Bathers at Asnières in 1884, before fully developing his signature style. However, three years later, he revisited the piece, refining it with his innovative pointillism technique—applying pure, unmixed colors in small dots to let them visually blend from a distance.

One of his key inspirations was the work of chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, known for his research on color perception. As a subtle tribute, Seurat painted six factory pipes in the background, cleverly arranging them to resemble paintbrushes. These chimneys belonged to a plant that used Chevreul’s candle-making process, making the tribute even more meaningful.

Art historians have long attributed around 30 paintings to Vermeer, but that number has recently dropped by one. Experts had long suspected that Girl with a Flute wasn’t actually painted by the Dutch master, and now, their theories have been confirmed.

Unlike Vermeer’s other works, this piece wasn’t painted on canvas but on a wooden panel. A team of researchers, curators, and restorers examined it closely and found noticeable differences in technique. The brushstrokes appeared looser and less precise than Vermeer’s usual style. However, the artist behind it was clearly familiar with his approach and even used similar materials.

One possibility is that Vermeer had an apprentice, even though he was believed to have worked alone. Some experts even suggest that the painting could have been done by his eldest daughter, Maria, who would have been between 15 and 20 at the time. Another theory is that Girl with a Flute was the result of a collaboration between Vermeer and another artist.

For years, art historians could only speculate about Rembrandt’s process when creating The Night Watch. But thanks to a special X-ray scan, new clues have been uncovered beneath the layers of paint—traces of calcium hidden under the brushstrokes.

This discovery revealed that Rembrandt sketched out his composition first using a chalk-rich paint, which the scan was able to detect. One surprising find? Originally, one of the men in the painting wore an elaborate feathered helmet, but at some point, the artist decided to remove it, altering the final look of the masterpiece.

For over a century, art historians have debated whether Vermeer relied on a camera obscura to achieve his stunningly precise compositions. His paintings are known for their flawless perspective, masterful layouts, and exceptional use of light, qualities that suggest he may have used optical tools.

One of the strongest clues is his handling of highlights and focus since some objects in the foreground appear slightly blurred, as seen in The Lacemaker. A camera obscura, which projects an image onto a surface, naturally captures these effects better than the human eye, making it a likely tool in Vermeer’s artistic process.

During Vermeer’s era, many artists were aware of the camera obscura, but few admitted to using it. At the time, relying on such a device might have cast doubt on an artist’s skill and creativity. While there’s no solid proof that Vermeer owned one, his close friend and neighbor, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, was a scientist known for crafting high-quality microscopes and lenses, making it possible that Vermeer had access to optical tools.

However, some experts argue that Vermeer didn’t need a camera obscura at all. Thirteen of his paintings contain tiny holes in the canvas, which seem to have been used to map out perspective with string. The debate over whether he used this optical device remains unresolved, keeping the mystery of his technique alive.

Cézanne created Still Life in 1865, during what’s known as his “dark” period, a time when his work was heavily influenced by Spanish Baroque art and the realism of Gustave Courbet. At this stage, he had yet to develop the signature style that would later define his career.

While examining the painting during a routine inspection, the museum’s chief restorer noticed tiny cracks in the paint. While aging cracks are common in 19th-century artworks, these stood out because they appeared in two specific spots, revealing white paint underneath. This was strange since Cézanne had only used small amounts of white on this particular canvas, raising questions about what might be hidden beneath the surface.

Curious about what might be hidden beneath the surface, the restorer decided to X-ray the painting. The scan revealed a portrait underneath Still Life, suggesting that Cézanne had painted over an earlier work. Based on the figure’s posture, experts believe it could be a self-portrait of the artist himself.

If this theory is correct, it may be one of Cézanne’s earliest known works. At the time he completed Still Life, he was only around 20 years old, making this discovery an exciting glimpse into his artistic beginnings.

Other iconic works, like Girl with a Pearl Earring and Lady with an Ermine, also have intriguing stories behind them.