I Refuse to Spend Every Weekend With My Husband’s Kids— Now My Marriage Is Falling Apart

On April 10, 1912, the RMS Titanic set sail from England. But this wasn’t the launch of a regular ship. The Titanic was the largest liner ever built at the time.

It was 882 feet long — that’s nearly the size of three soccer fields! And measured from the hull to the top of the smokestacks, the ship was an impressive 175 feet tall! That’s the size of a 17-story building. Deemed “unsinkable,” it took 3,000 workers almost 3 years to build.

But a mere four days into its very first voyage, at 11:40 PM, the ship collided with an iceberg and was lost beneath the waves of the Atlantic Ocean. It took the liner only 2 hours and 40 minutes to sink. And of more than 2,200 passengers and crew members on board, only 706 survived.

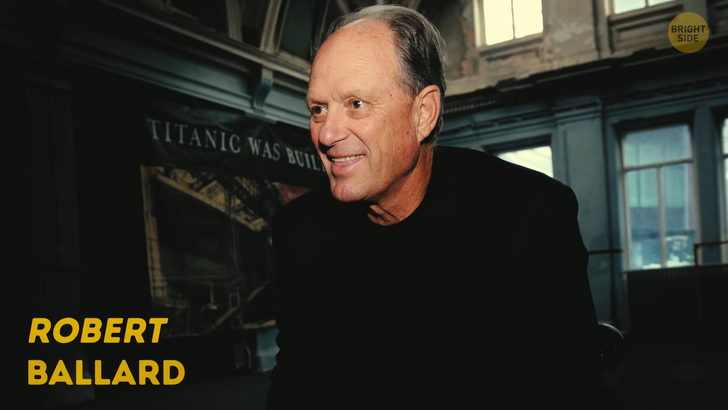

The wreck would remain lost for another 73 years, hiding its many secrets within the frigid Atlantic waters. And if it wasn’t for a man whose whole life had been devoted to exploring the sea, the giant ship might have remained lost for a lot longer. That man was Robert Ballard.

As a child, Ballard was obsessed with the ocean. This fascination started when he was just 12 years old. That’s when he watched a film adaptation of Jules Verne’s science fiction novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. It had everything to spark a young person’s imagination — from adventure and strange creatures to a powerful underwater vehicle called the Nautilus. It could travel anywhere in the world you wanted to go.

From that moment, life on dry land was no longer in Ballard’s future. When he was 23, he was assigned to the Deep Submergence Group. There, he helped develop techniques to search the ocean floor. His biggest accomplishment was the creation of Alvin. It was a small, easy to maneuver submarine that could carry three people. It also featured an external mechanical arm, designed to gather underwater samples while the crew remained safe and dry inside.

Alvin the submarine quickly proved useful for a variety of tasks. For example, once, it was used to track down an aircraft that had crashed into the sea. But the vessel experienced a series of setbacks. In one case, it was attacked by a swordfish, which caused the submarine to resurface quickly. The swordfish, still stuck in the outer skin of the submarine, became that night’s dinner.

And in October 1968, the submarine was being lowered into the water when the cables holding it snapped, sending it careening into the ocean along with three crew members on board! And because the small vessel was still open, it immediately filled with water and quickly began to sink! Luckily, the crew managed to escape, but Alvin was gone. Bad weather hampered multiple attempts to recover the vessel. It wasn’t until the following year that it was finally returned to the surface.

In time, Alvin would be improved. Its hull would be strengthened by titanium, giving it a higher depth rating, thus making it even better suited for ocean exploration. The specialized submarine would come in handy in many of Ballard’s 100-plus expeditions. The man was one of the first to explore an underwater mountain chain called the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the Atlantic Ocean. And when he found thermal vents in the Galápagos Rift in the late 70s, he also helped discover and document the process of chemosynthesis. That’s a complicated chemical synthesis of food energy by bacteria.

But his biggest discovery was still to come. Ballard claimed he’d never been a “Titanic fanatic.” But he eventually became obsessed with finding the ship after watching other explorers try and fail. As he said, “Titanic was clearly the big Mount Everest at the time. Many others had tried. Many that I thought would have succeeded or should have succeeded but didn’t.” Ballard began thinking about finding the ship as early as 1973.

And four years later, he actually made an attempt. He used the deep-sea salvage vessel Seaprobe, which was a drillship equipped with cameras and sonar. But he was forced to give up when the drilling pipe broke. It just wasn’t his time. In the early 80s, a Texas oilman named Jack Grimm tried to find the wreck on 3 different occasions. Once, Grimm was actually right over the Titanic, but his equipment failed to detect it! That’s what we call extreme bad luck.

Ballard was just biding his time. He needed a plan. And some help. The first issue was getting down to the bottom of the Atlantic. The furthest down he had ever traveled before was 20,000 feet. And this trip took him three hours. And that didn’t include the way back up!

Ballard knew he could use Alvin, already enhanced with a titanium hull to withstand the pressure of the ocean. But he also needed something that didn’t require him to actually go down with it. An un-piloted remote-controlled submarine would be ideal. But first, he would have to create one. He reached out to the authorities, hoping they would provide funding for his project. And though officials had no interest in the Titanic, they were willing to help.

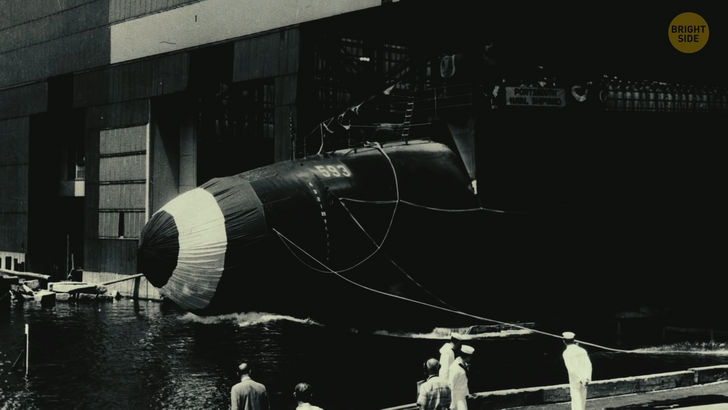

Ah! But there was a catch. Ballard had to first focus on tracking down two submarines, the Thresher and the Scorpion, which had sunk to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean in the 1960s. The authorities were hoping to study them to find out why they had sunk in the first place. They also wanted to know if they could be recovered or if it was safe to leave them on the ocean floor. Only when he had successfully completed this task would he be free to use any remaining time on his contract to find the Titanic.

With no other options for funding, Ballard took the offer. He got to work. First, he created two new devices. Argo was an un-piloted deep-towed undersea video camera sled. It was designed to take photos and record videos from a series of cameras mounted on it. It could work at depths of up to 20,000 feet, and it could also explore nearly 98% of the ocean floor.

Argo was supposed to be tethered to a boat. As the boat moved, Argo would be pulled behind, floating just above the ocean floor. The camera would then transmit images to the surface. The second device was a small robotic vehicle called Jason Jr. It was also controlled remotely, which allowed the crew inside a submarine, like Alvin, to get closer to and photograph underwater objects.

Ballard was now ready. He knew he had to find those submarines quickly. And it didn’t take him long. Much to his relief, the search was relatively simple, and he was able to fulfill his obligations with 12 days to spare.

With almost two weeks to devote to finding the Titanic, he set out to explore the ocean. He focused the search close to Newfoundland, Canada, pulling Argo along the ocean floor and reviewing the images it collected.

And after a few days of nothing, they eventually found riveted hull plates and a boiler. Could this be it?! The next day, a ship’s large bow was revealed. On September 1, 1985, Ballard and his fellow crew members realized they had finally found the infamous ship.

The discovery resulted in a mix of emotions. Ballard was excited to be the first to find the Titanic’s final resting place. But he was also overwhelmed by the sense of grief for those who had suffered when the ship had gone down. Over the next four days, the crew explored the wreck. They found the crow’s nest, from where the iceberg had first been spotted.

Plus, there was finally evidence of how the massive ship had split in two before sinking — with both halves of the ship found. There was furniture and dinnerware. And, sadly, several leather shoes of those who hadn’t made it to safety were scattered about the ocean floor. Ballard succeeded where others had failed and became an instant celebrity around the world. You’d think that locating the Titanic would be enough for one man. But not for Ballard.

In 2019, he took on the challenge of solving another mystery: the disappearance of Amelia Earhart. Earhart had attempted to be the first woman to fly around the world. Unfortunately, she disappeared somewhere over the Pacific Ocean in 1937. She and her plane were never found.

Ballard hoped that his luck with the Titanic would help with finding where Earhart had gone down. But his expedition failed to find anything. And though Robert Ballard has found more shipwrecks than anybody else, it’s only the tip of the iceberg. It’s estimated that there are over three million shipwrecks in the ocean, and Ballard has only located 100 of them.

Now, in his 80s, the man is hoping to encourage young people to continue his work of exploring the ocean and its many mysteries. In 1989, he started the Jason Learning Project to inspire grade school students to pursue science, technology, engineering, and math. He also has his own research vessel called the E.V. Nautilus after the name of the submarine in Jules Verne’s novel. A fitting tribute to the story that inspired his career.