Helen Hunt, 60, Stuns During Her Latest Appearance, and Her Lips Become the Center of Attention

Can you tell me what date it is today? Piece of cake. You just look at your smartphone, and voilà: you immediately know the day, month, and year. But, was it always this easy to tell the date? Did the ancient people even have the concept of a year that lasts 365 days?

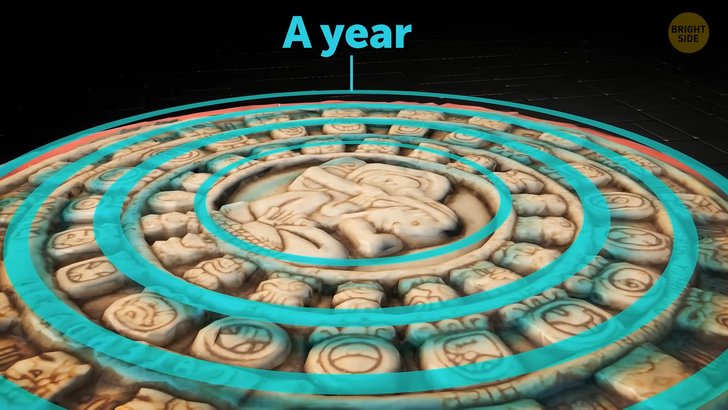

Yes and no. Mayan calendars had cycles. That’s close to what we call a year. But the Mayan cycle was much longer: 819 days. And this is where the mystery begins. 819 days compared to what? When does this calendar begin, and when does it end?

Scientists were asking themselves this question for decades. They discovered and deciphered the Mayan calendar during the 1940s. Recently, two American scientists [John Linden & Victoria Bricker] came forward with a solution.

So, what did they do differently from their predecessors? The duo deciphered the code by broadening their thinking. They expanded the calendar from 819 days to full 45 years. That’s 20 times longer than the original cycle. And a pattern started to emerge.

This was a major breakthrough because the Maya told time in a complicated way. You can forget about the easy-to-read Arabic numerals we have today. These ancient people used glyphs. These are tiny images that represent characters. Something like the icons on your desktop or universal symbols.

When you see a little dot with three curved lines above it, you know there is a Wi-Fi network available. The Mayan calendar used glyphs that represented animals or natural phenomena. For example, there were symbols for a jaguar and an eagle. Each glyph marked one day.

Each cycle is repeated four times [819 X 4]. Let’s call these four cycles blocks. The Mayas colored each block differently. Scientists thought these colors corresponded to the four cardinal directions. Red was east, white — north. West was black and, finally, yellow marked south. But then the 1980s came. Yeah, this was a weird decade.

The calculations were all wrong. Researchers determined that the colors were associated with the position of the Sun in the sky. It turned out that the color yellow represented the highest point of the Sun, which is called a zenith. White was the lowest point, called the nadir. It seems that the calendar showed just how good the ancient Mayas were at astronomy.

This is most evident at Chichén Itzá. This principal Mayan city is located on the Yucatán Peninsula [Mexico]. There stands an impressive step pyramid. It is dedicated to the Feathered Serpent deity. And its alignment is perfect. Something marvelous happens here twice a year, during the equinoxes [March & September] These are the times when the Sun shines directly over the Equator. On these two dates, the day and night last the same.

At the site of the pyramid, sunlight first illuminates the sculpture of the serpent head at the base of the structure. Then it makes its way up the 91 steps. This creates the illusion that a snake is slithering down the pyramid. Even today, people gather to witness the sight. And it must have been more impressive when the Mayas completed the structure [1050 — 1300 CE].

Do you know what a synodic period is? Neither do I. But Mayan astronomers did. A synodic period is the time that passes before a stellar body does a full lap. For example, this is the period between two full Moons.

When you look from Earth, this period lasts roughly 30 days. And the Mayas were looking at the skies non-stop. They carefully noted the synodic periods of all planets. From Venus to Saturn, these ancient astronomers kept records of nearly all celestial bodies. But what does this have to do with their calendar?

The American researchers’ calculations revealed the link. Let’s take the planet closest to the Sun as an example [Mercury]. Its synodic period is 117 days. Multiply that by seven and you get which number? Exactly 819 [117 X 7 = 819]. Coincidence? Definitely not. Because synodic periods of other planets also neatly match the magical figure [819].

But this is not visible from a single Mayan cycle. Scientists had to expand it several times to discover the pattern. There is a reason why no one could decipher the code for so long. They were focused on a single planet. The trick was to add the Mayan calculation for all the planets. Researchers just needed to see the bigger picture.

This brings us to the year 2012. Can you remember that some people thought that the world would end on December 21st? That turned out to be a bust. We are alive and well now. But what started this false rumor? The Mayan calendar, of course. You see, these ancient people based their calendar on long periods of all the planets. That included a lot of complicated math and a lot of multiplying.

This [2012] was simply the time when their cycle ended. It is known as the Long Count. This period is the same as our year. For the Mayas, 2012 was something like the 31st of December for us. Just an end of a cycle in which they measured time. So there was no need to panic. Those New Year’s Eve parties might be a bit wild, but the world doesn’t end on January 1st.

The Mayas stretched more than their calendar. Rubber was the name of the game. Yes, you’ve heard it correctly. These ancient people were making different grades of rubber three thousand years before one famous American did [Charles Goodyear]. They would extract natural latex from the rubber tree. This is a milky substance that can be turned into rubber.

And they weren’t the only ones. Scientists found evidence that their neighbors, the Aztecs and the Olmecs, did the same. But what did they do with rubber? They didn’t need car tires, definitely. But it’s cool to have a nice pair of sandals for the beach. The Spanish wrote about rubber-sole footwear that natives wore. Sadly, scientists still haven’t found them. That would be a big step for archeology.

So, the Maya were playful with rubber; literally. Researchers guess that they produced balls from latex. These were bouncy and ranged in size from a softball to a soccer ball. A typical Mayan ballgame [pitz] involved two hoops. You must be thinking basketball, but not quite. The hoops were set on walls, 23 feet high. Compare that to the NBA standard of 10 feet. And the hoop was the other way around.

There is also a sweet side to the story of the Mayas. These ancient people enjoyed chocolate. In fact, the modern word chocolate probably comes from their language [xocolatl]. This meant: bitter water. Ok, you get the bitter part, but why water? The Mayas didn’t produce chocolate in the form we know it today. They didn’t make bars of chocolate; they drank it.

Smashed cocoa beans made for excellent drinks. The Mayas perfected the mixture over time and even added spices. Anyone up for a fiery chocolate drink with stew peppers and cornmeal? Who knows, maybe this beverage actually tasted well. Cocoa beans were sacred and used as a currency. Researchers believe all social classes got to enjoy it. Free chocolate for all sounds nice even today.

But where did the Mayas get clean water for their cocoa drinks? From the oldest-known filtration system in the western hemisphere. It was based on zeolite. These are minerals that contain aluminum and silicone compounds.

And guess what? Modern air and water purifiers still use this material. Mayan tech wins yet again. Back in Europe, Roger Bacon developed a sand filtration system in 1627, some 1,800 years after the Mayas. But what about regions without rivers, lakes, or springs? Mayan engineers had it all figured out. Rainwater.

They would carve out large reservoirs in the limestone bedrock. Then, they would coat these underground caves with a layer of a watertight material. The final step was to make small channels that collected water from the hills above. Scientists estimated that just one of these reservoirs could hold on average ten thousand gallons of rainwater. Enough to fill 55 modern hot tubs.