My Stepkids’ Mom Said I Had No Right to Call Them ‘My Kids’—But I Set Her Straight

In a revealing twist for maternal mental health, a new study shows that postpartum depression can begin long before the baby is born. For women expecting a baby, this finding brings not only understanding, but also hope: the possibility of detecting and treating the problem before it rears its head.

Content is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for medical advice. Seek guidance from your doctor regarding your health and medical conditions.

For decades, postpartum depression was viewed as a temporary emotional imbalance, but in reality, it is a serious medical condition that affects 1 in 7 women and can profoundly compromise the mother’s well-being, her bond with her baby and her family environment.

Symptoms include sadness, frequent crying or tearfulness, loss of interest or pleasure in life, loss of appetite, loss of motivation, irritability, fatigue, anxiety, poor sleep, and feelings of hopelessness and guilt.

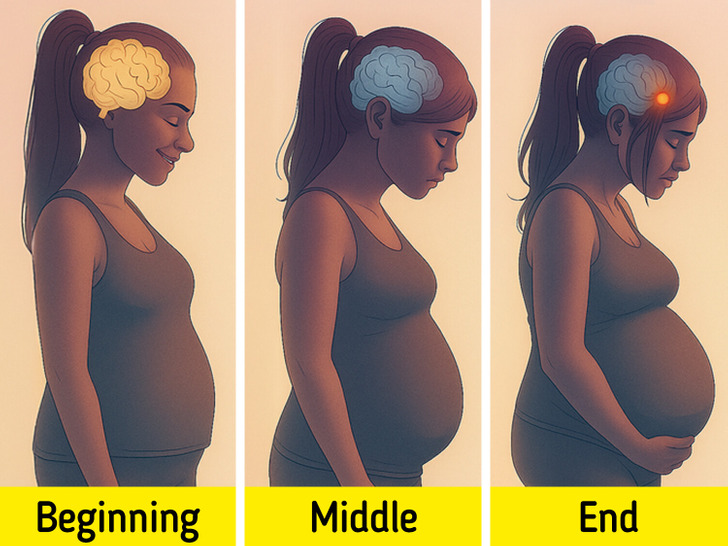

Until now, this condition was thought to appear in the weeks following delivery, fueled by sleep deprivation, physical fatigue and hormonal turmoil. However, new evidence indicates that the brain begins to transform during pregnancy, paving the way for possible mood disorders.

A new study analyzed brain images of 118 women — 88 pregnant and 30 non-pregnant — during the third trimester and after delivery. What they found was both revealing and disturbing: specific structural changes in key brain regions before the baby was born.

In particular, an increase in the volume of the amygdala — a region linked to emotion processing and stress response — was detected in women who later developed symptoms of postpartum depression. Alterations were also observed in the hippocampus, a structure associated with memory and emotional regulation, especially in those who had undergone more traumatic births or higher levels of stress.

This suggests that the neurological “signature” of postpartum depression may be present long before delivery, challenging the classical notion that this condition begins only after having a child.

One of the most hopeful revelations of the study is the possibility that these transformations may be detectable by neuroimaging before delivery. In other words, we could anticipate the onset of postpartum depression with specific clinical tools, such as brain MRI scans.

This opens a new window in preventive medicine: if we identify early neurobiological markers, it is possible to offer personalized interventions to the most vulnerable mothers-to-be — from psychological support to hormonal regulation — before symptoms set in.

In addition, researchers are studying biomarkers in the blood in order to develop a blood test that measures the levels of the neurosteroids to estimate a person’s risk of PPD.

Postpartum depression not only affects the sufferer: it can also interfere with the baby’s emotional, social and cognitive development. When a mother fails to connect emotionally with her child because she feels overwhelmed or disconnected, that early bond -key to parenting- can be damaged.

Therefore, these findings are not only relevant from a medical perspective: they have social and cultural implications. Investing in perinatal mental health is not a luxury, but a necessity. Motherhood begins in the body, but also in the brain, and every transformation needs accompaniment and understanding.

Much remains to be discovered: why some women develop symptoms and others do not, exactly how long post-pregnancy brain changes last (some studies indicate that they may extend for more than two years), or how factors such as prior psychiatric history and social context influence the equation.

What is clear is that we are facing a paradigm shift. The neurobiology of childbearing is not static, uniform, or easily predictable, but it can be understood and addressed with increasingly sophisticated scientific tools. And that is excellent news.

For a long time, postpartum depression was thought to be simply an emotional reaction to the challenges of the postpartum period. Today, science shows that there is a deeper, more complex story: one that begins long before childbirth, written in the innermost folds of the brain. Understanding this not only relieves the guilt of many women who feel bad “for no reason,” but also opens the door to more accurate diagnoses and truly empathetic support.

And if you want to continue exploring how science is transforming our understanding of motherhood, you can read this other article.